The forgotten medieval habit of 'two sleeps'

It was around 23:00 on 13 April 1699, in a small village in the north of England. Nine-year-old Jane Rowth blinked her eyes open and squinted out into the moody evening shadows. She and her mother had just awoken from a short sleep.

Mrs Rowth got up and went over to the fireside of their modest home, where she began smoking a pipe. Just then, two men appeared by the window. They called out and instructed her to get ready to go with them.

As Jane later explained to a courtroom, her mother had evidently been expecting the visitors. She went with them freely – but first whispered to her daughter to "lye still, and shee would come againe in the morning". Perhaps Mrs Rowth had some nocturnal task to complete. Or maybe she was in trouble, and knew that leaving the house was a risk.

Either way, Jane's mother didn't get to keep her promise – she never returned home. That night, Mrs Rowth was brutally murdered, and her body was discovered in the following days. The crime was never solved.

Nearly 300 years later, in the early 1990s, the historian Roger Ekirch walked through the arched entranceway to the Public Record Office in London – an imposing gothic building that housed the UK's National Archives from 1838 until 2003. There, among the endless rows of ancient vellum papers and manuscripts, he found Jane's testimony. And something about it struck him as odd.

Originally, Ekirch had been researching a book about the history of night-time, and at the time he had been looking through records that spanned the era between the early Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution. He was dreading writing the chapter on sleep, thinking that it was not only a universal necessity – but a biological constant. He was sceptical that he'd find anything new.

So far, he had found court depositions particularly illuminating. "They're a wonderful source for social historians," says Ekirch, a professor at Virginia Tech, US. "They comment upon activity that's oftentimes unrelated to the crime itself."

But as he read through Jane's criminal deposition, two words seemed to carry an echo of a particularly tantalising detail of life in the 17th Century, which he had never encountered before – "first sleep".

"I can cite the original document almost verbatim," says Ekirch, whose exhilaration at his discovery is palpable even decades later.

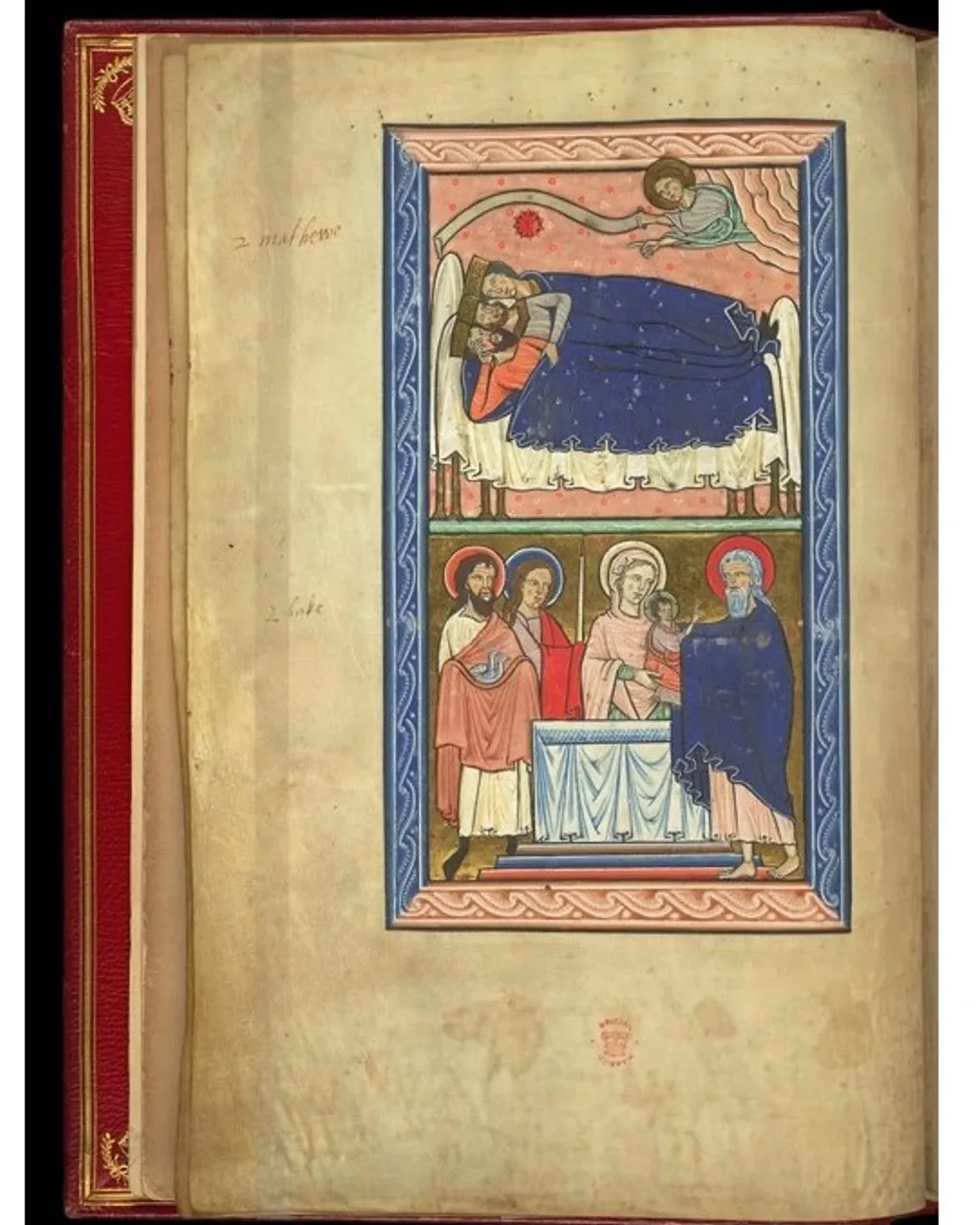

In the Middle Ages, communal sleeping was entirely normal – travellers who had just met would share the same bed, as would masters and their servants (Credit: British Library)

In her testimony, Jane describes how just before the men arrived at their home, she and her mother had arisen from their first sleep of the evening. There was no further explanation – the interrupted sleep was just stated matter-of-factly, as if it were entirely unremarkable. "She referred to it as though it was utterly normal," says Ekirch.

A first sleep implies a second sleep – a night divided into two halves. Was this just a familial quirk, or something more?

An omnipresence

Over the coming months, Ekirch scoured the archives and found many more references to this mysterious phenomenon of double sleeping, or "biphasic sleep" as he later called it.

Some were fairly banal, such as the mention by the weaver Jon Cokburne, who simply dropped it into his testimony incidentally. But others were darker, such as that of Luke Atkinson of the East Riding of Yorkshire. He managed to squeeze in an early morning murder between his sleeps one night – and according to his wife, often used the time to frequent other people's houses for sinister deeds.

When Ekirch expanded his search to include online databases of other written records, it soon became clear the phenomenon was more widespread and normalised than he had ever imagined.

For a start, first sleeps are mentioned in one of the most famous works of medieval literature, Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales (written between 1387 and 1400), which is presented as a storytelling contest between a group of pilgrims. They're also included in the poet William Baldwin's Beware the Cat (1561) – a satirical book considered by some to be the first ever novel, which centres around a man who learns to understand the language of a group of terrifying supernatural cats, one of whom, Mouse-slayer, is on trial for promiscuity.

But that's just the tip of the iceberg. Ekirch found casual references to the system of twice-sleeping in every conceivable form, with hundreds in letters, diaries, medical textbooks, philosophical writings, newspaper articles and plays.

The practice even made it into ballads, such as "Old Robin of Portingale. "…And at the wakening of your first sleepe, You shall have a hot drink made, And at the wakening of your next sleepe, Your sorrows will have a slake…"

Biphasic sleep was not unique to England, either – it was widely practised throughout the preindustrial world. In France, the initial sleep was the "premier somme"; in Italy, it was "primo sonno". In fact, Eckirch found evidence of the habit in locations as distant as Africa, South and Southeast Asia, Australia, South America and the Middle East.

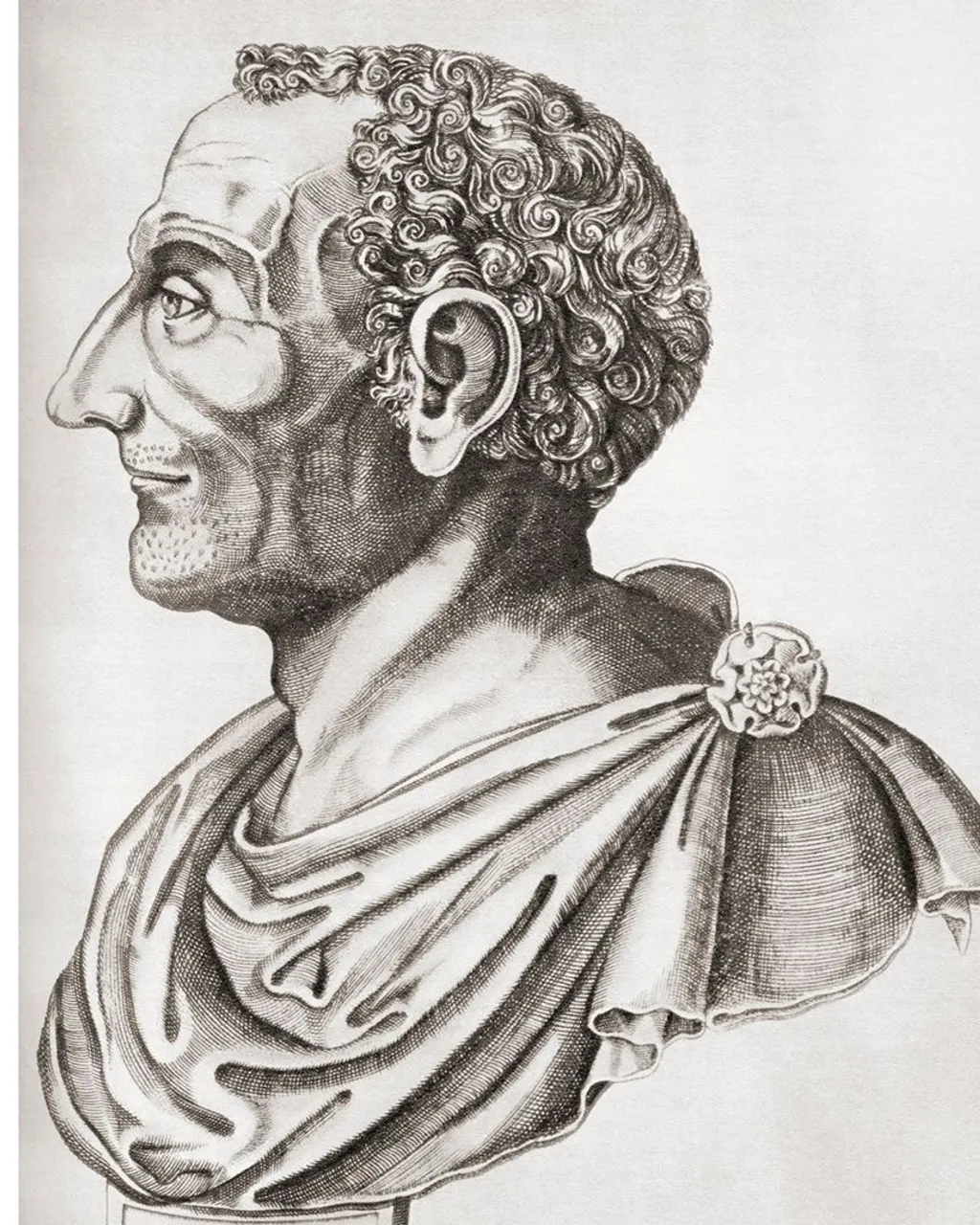

Like many Romans, the historian Livy may have been a practitioner of biphasic sleep – he alludes to the method in his magnum opus, The History of Rome (Credit: Alamy)

One colonial account from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1555 described how the Tupinambá people would eat dinner after their first sleep, while another – from 19th Century Muscat, Oman – explained that the local people would retire for their first sleep before 22:00.

And far from being a peculiarity of the Middle Ages, Ekirch began to suspect that the method had been the dominant way of sleeping for millennia – an ancient default that we inherited from our prehistoric ancestors. The first record Ekirch found was from the 8th Century BC, in the 12,109-line Greek epic The Odyssey, while the last hints of its existence dated to the early 20th Century, before it somehow slipped into oblivion.

How did it work? Why did people do it? And how could something that was once so completely normal, have been forgotten so completely?

A spare moment

In the 17th Century, a night of sleep went something like this.

From as early as 21:00 to 23:00, those fortunate enough to afford them would begin flopping onto mattresses stuffed with straw or rags – alternatively it might have contained feathers, if they were wealthy – ready to sleep for a couple of hours. (At the bottom of the social ladder, people would have to make do with nestling down on a scattering of heather or, worse, a bare earth floor – possibly even without a blanket.)

At the time, most people slept communally, and often found themselves snuggled up with a cosy assortment of bedbugs, fleas, lice, family members, friends, servants and – if they were travelling – total strangers.

To minimise any awkwardness, sleep involved a number of strict social conventions, such as avoiding physical contact or too much fidgeting, and there were designated sleeping positions. For example, female children would typically lie at one side of the bed, with the oldest nearest the wall, followed by the mother and father, then male children – again arranged by age – then non-family members.

A couple of hours later, people would begin rousing from this initial slumber. The night-time wakefulness usually lasted from around 11:00 to about 01:00, depending on what time they went to bed. It was not generally caused by noise or other disturbances in the night – and neither was it initiated by any kind of alarm (these were only invented in 1787, by an American man who – somewhat ironically – needed to wake up on time to sell clocks). Instead, the waking happened entirely naturally, just as it does in the morning.

The period of wakefulness that followed was known as "the watch" – and it was a surprisingly useful window in which to get things done. "[The records] describe how people did just about anything and everything after they awakened from their first sleep," says Ekirch.

Source: BBC News