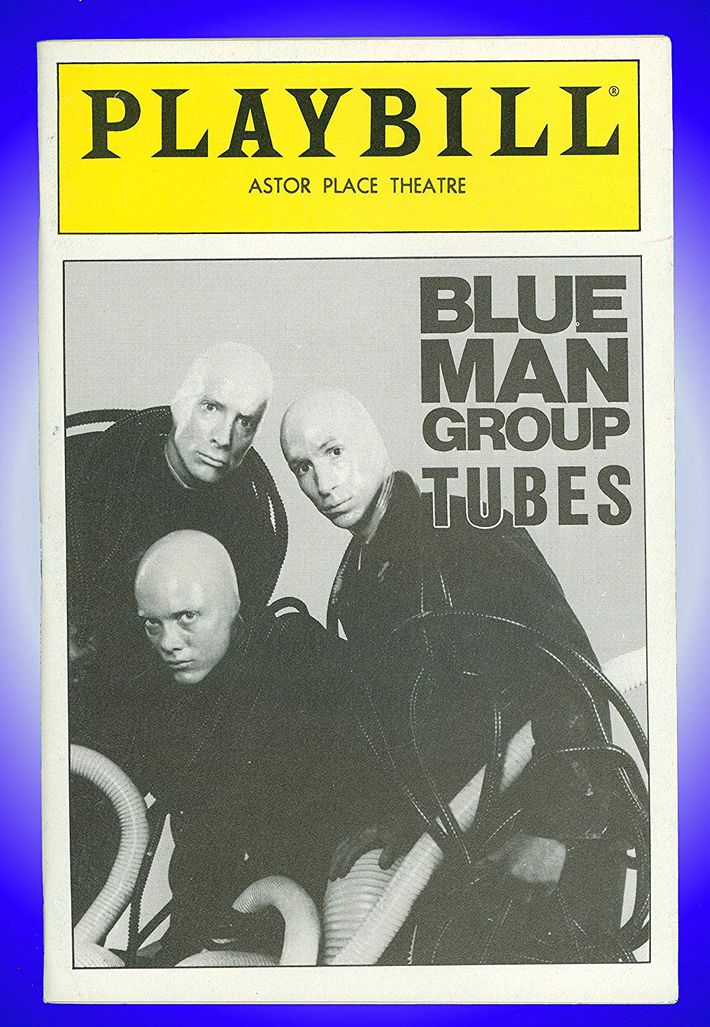

How Blue Man Blew Up

The wild success of a show starring strange bald men painted in Yves Klein blue.

On May 21, 1988, eight people carried a coffin into Central Park to conduct a “funeral for the ’80s.” Inside it were items meant to represent the culture of the decade: a Rambo doll, tiny figures wearing suits (yuppies), bags of a white substance resembling crack. The participants, most of whom had painted their skin blue, piled the objects into a metal drum along with some flash paper, which they lit on fire. They called themselves the Blue Man Group.

Within months, the group of Blue Men had been winnowed down to three: Chris Wink, Matt Goldman, and Phil Stanton. Over the next few years, with input from a circle of art-school kids and musicians, they would bring their constantly evolving act to many spots around the city — they played with vaudeville at King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut, experimented with flying paint at La MaMa, and eventually landed at Astor Place Theatre. The three characters were general outsiders, unfamiliar with our customs and unable to speak but endlessly curious and eager to connect; they also caught a heroic number of food items in their mouths. “The word on the street was we were nuts,” says Larry Heinemann, who played with the group on instruments including the Chapman Stick.

There have since been shows in Boston, Chicago (where Fred Armisen was a drummer with the Blue Men early in his career), Las Vegas, Orlando, and beyond, as well as commercial campaigns featuring the original trio and tours with Moby, David Bowie, and Busta Rhymes. This past November, the Astor Place show marked its 30th year — one of the most successful Off Broadway runs of all time.

That this undeniably unusual show found an audience when it launched — during the rise of rave culture and a few years after Burning Man debuted on Baker Beach — made a certain kind of sense for the era. But its lasting success has surprised no one more than the founders themselves. “From the beginning, we weren’t just trying to be pure — to make art and gaze at our navels,” says Wink. “But it’s not like we expected to get as far as we did. It would have been insane to think that.”

Going Blue

Wink and Goldman met while attending Fieldston School in the Bronx. In their 20s, they shared an apartment on the Upper West Side. Goldman was a software producer; Wink was a trend forecaster, drummer, and caterer at Glorious Foods — which is where he met Stanton, an aspiring actor.

Juliet Lofaro, props coordinator, 1991–94: I was living with Chris and Matt. Chris grew up in the apartment, and one day I found a book he made as a kid called My Blue World, with pictures of a blue man.

Larry Heinemann, original Chapman Stick player: As long as I knew Chris, the idea was in his head — Wouldn’t it be cool to see a bunch of blue men walking down the street?

Chris Wink, co-founder: It was just this idea of getting blue and walking around seeing what happened as a social experiment. It wasn’t really fleshed out.

Heinemann: Around 1986, Chris and Matt started holding salons. We were all charged with sharing something — a song, a photo, an idea. A theme was our disappointment with what early-’80s music had morphed into.

Wink: Punk had died, Studio 54 was closed, and it was the Reagan ’80s. That was when the term yuppie started. MTV came along and turned all these cool bands into singing monkeys. For us, the decade didn’t seem cool.

Flyer for an early show, ca. 1990. Photo: Courtesy of Blue Man Group

Heinemann: We thought performance art would be the next cultural tidal wave.

Matt Goldman, co-founder: We wanted to build a movement of people who wanted to be creative even if it was in ways that didn’t fit society’s definition.

Wink: We used our apartment as a home base — we got rid of all the furniture.

Heinemann: At the salons, the Blue Man would come up — maybe this could be something? At one, Chris smeared blue makeup on his head. We were like, “That’s cool, but your hair looks weird.” The next salon, he had a bald cap.

Wink: It’s not like we were saying, “What’s the character’s backstory? Should he be green or blue?” It was more mysterious than that. We picked blue because it felt right.

Goldman: I have a visceral recollection of the first time the three of us got bald and blue. We went on the roof and just sort of looked at each other, realizing this character was special.

Heinemann: Then it became, “What are we going to do with this?”

Lofaro: The funeral for the ’80s came about in the living room.

The first BMG appearance, on MTV, in 1988. Photo: YouTube

Wink: We figured if we had a bold statement — “The ’80s are over” — and if MTV covered it, it’d be true. We wrote a press release and invited Kurt Loder.

Heinemann: Kurt actually covered it, which was crazy for our first thing.

Goldman: He made it seem like if you missed this thing, you were a loser.

An Open-ended Run

A few months later, the group organized another “happening,” as they called it, outside the Copacabana Club on East 60th Street. They used velvet ropes to set up a ten-by-ten-foot square on the sidewalk — which they called Club Nowhere — and invited anyone who wanted to party inside for free. “Club Nowhere was the last of the verbal Blue Man events,” Heinemann says. “Around then, we discussed how the character doesn’t talk.” They soon began developing a series of short performance pieces inspired by sources as varied as fractal geometry and the Japanese drumming troupe Kodo.

|

|

Read More Here: Vulture